Waiting for the stories

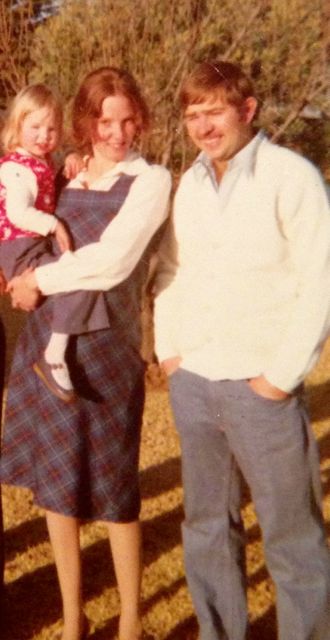

When I was 2 years old, my dad went to war.

It’s the kind of thing that you think of in movie terms really, despite the fact that about over 35 active conflicts or warzones in the world at any one time these days.

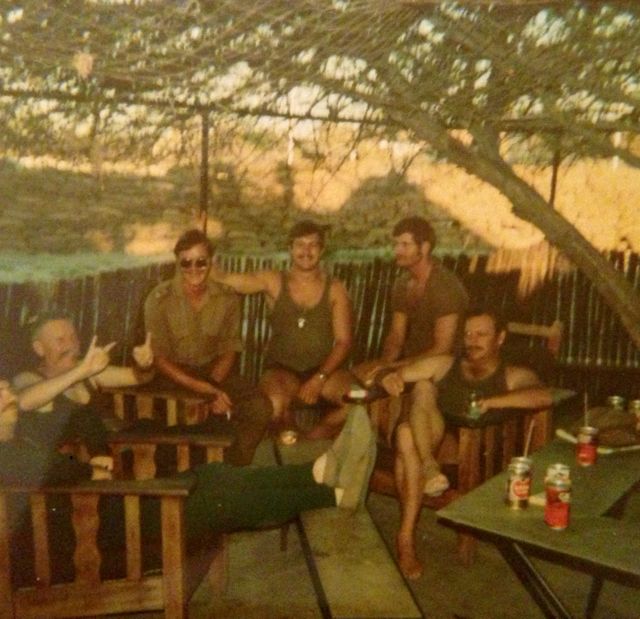

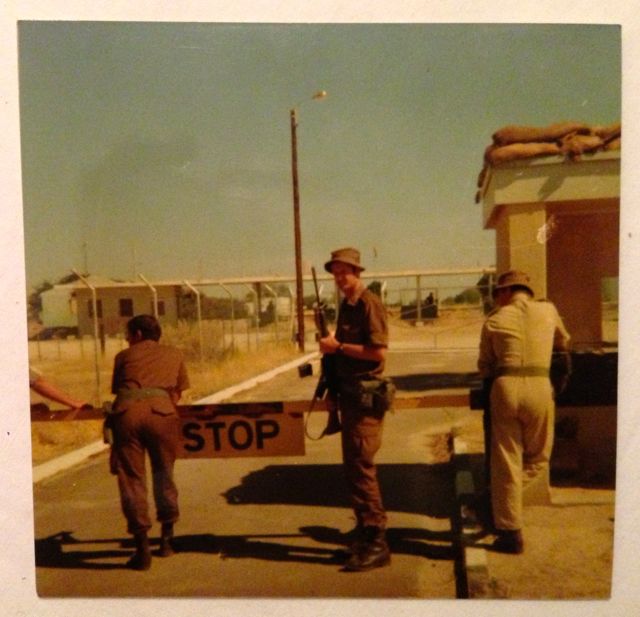

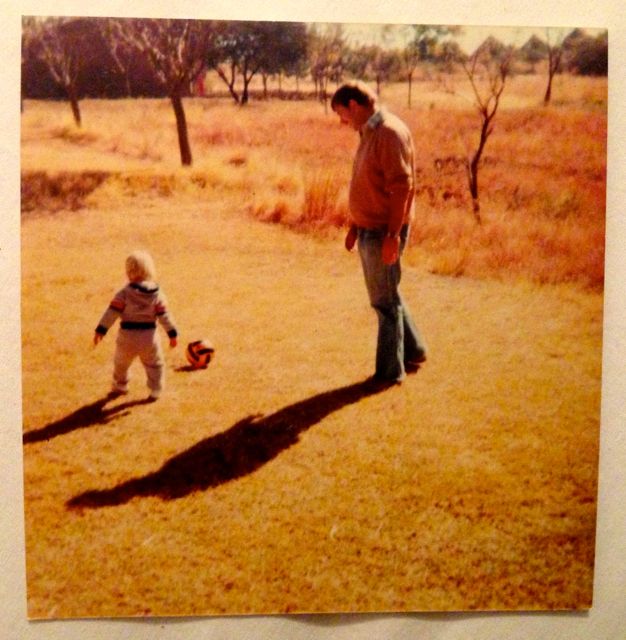

I don’t really think of it in my little realm of experience at all, but it is true. My father spent 3 months as a soldier in an active war – the average active duty for South African soldiers in the 70’s & 80’s on the so-called Border war in Angola.

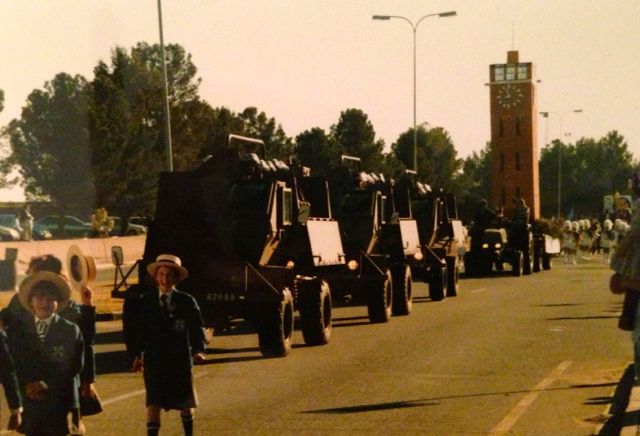

He carried a gun and rode tanks and sent anti-landmine trucks ahead of convoys and rode in Huey-type choppers at tree-top height along the Caprivi strip on dawn patrol. And he never said a word about it to me.

Not a word.

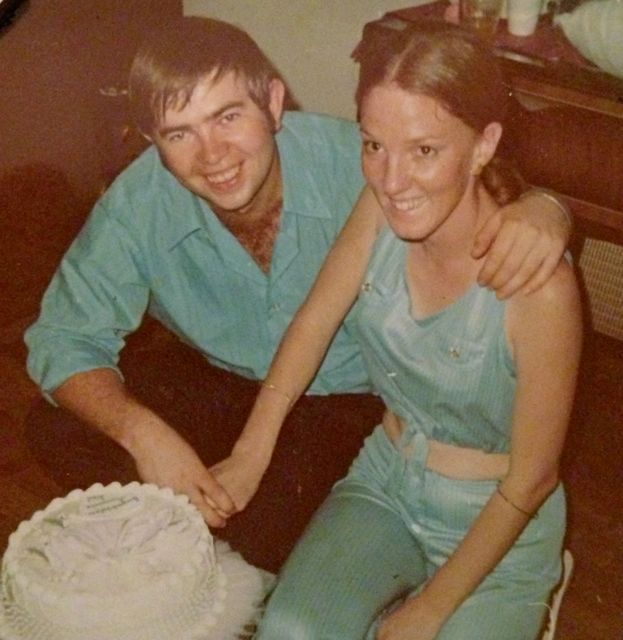

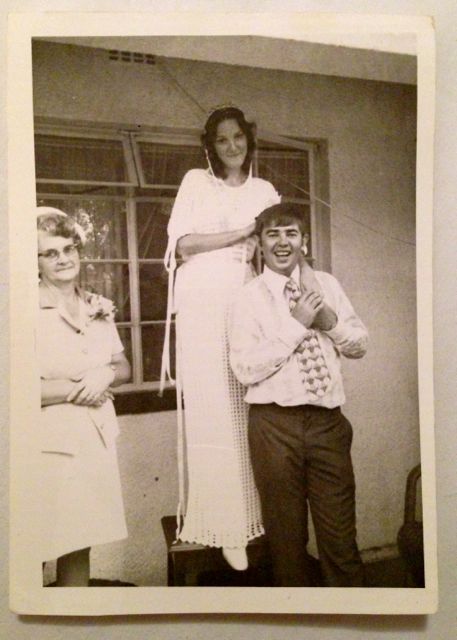

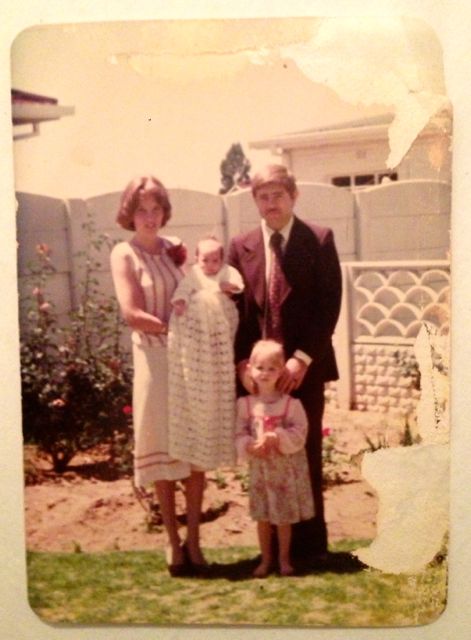

I knew he had been, later, because I was told. I don’t really remember anything from that time although my mom says I didn’t really recognize my dad immediately when he came home. How heart-breaking that must have been for both of them.

I knew about the war growing up because it was a thread through the world of my childhood. Peoples’ sons were drafted, they were scared of Basics (a 6 week Basic training session that newby soldiers did – a lot of running and general military grinding down of soldiers), they were scared of the Border. I knew that my dad considered going back to the Border at some stage – although I didn’t really know what that meant. I remember overhearing snippets of conversation from the lounge about it and somehow in my head the Border became a kind of giant trampoline thing that people went and jumped on. It made little sense to me, but then did it really make sense to anyone? Men came back from the Border different or not at all. It didn’t seem to make any sense to any of them either, but they still went.

I do remember, quite clearly actually, later on – I was maybe 4 or 5 by then – that every 7pm news bulletin ended with a slow scrolling list of the names of soldiers killed on the Border that day or week. I remember that feeling, waiting to see how many had died this time. Sensing my dad reading them so see how many he knew. Understanding only obliquely really, the trauma that accompanied each name on that list, the families behind each one. Carrying the sense of it with me, despite not fully understanding it yet.

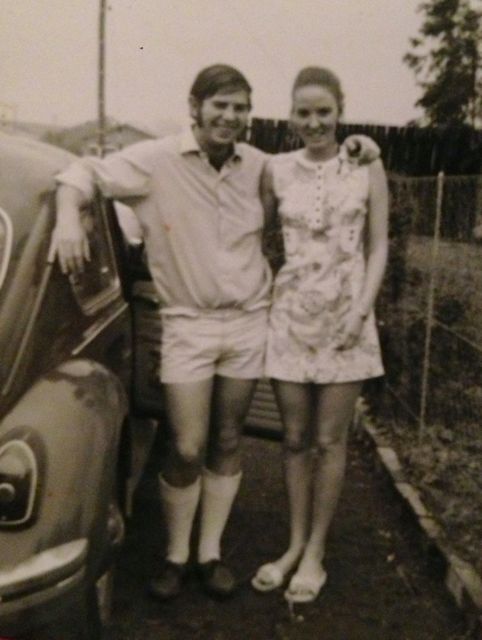

My dad was 28 years old when he went to the border. Twenty-eight. My brother (the brat!) is older than that already, and I shudder to think of sending him off to war even now when it is not a reality. How did they do it back then, knowing that the list at the end of the news was an everyday reality. How did you watch someone you love get on a bus or a train and let them go?

There is a whole well of strength there, on both sides of that equation, that I truly don’t know if I could ever access. And that I am bowed down by .

For most of my life-time I’ve wondered about that time. What was it like, being a grown-up when those were your choices? What happened inside and out, in times like that.

But the good old South African version of the stiff upper lip kept everyone in check and stony silence – manne, ons gaan aan (trl: men, we carry on). It was never talked about. It was swiftly kicked under the carpet, drinks were served and hair was permed and the 80’s carried on regardless of the pain.

And then suddenly, unexpectedly, the dam broke over Easter. The barefoot mountain man and I were in Pringle Bay with the parentals and the Phoebe-dog and the girls (for a bit of the weekend) and over dinner at a cosy little Pringle bar and restaurant – a locals hang-out – with the wind and rain lashing the first-floor windows and the wood-burning stove warming my back like a cat, something on a universal time-piece ticked over somewhere and for the first time I can recall, my folks talked about that time.

We’d been discussing the Barefoot man’s studies (he’s doing psych) and my mom had mentioned the shock of having been to a mental asylum as a 2nd year Nursery school student teacher – she’d felt so shocked at seeing an albino person that she felt ill – that Apartheid government was very good at keeping things like albinism in the dark – no need to publicise things that would undermine their neatly wrapped up fairy-stories about racial separation.

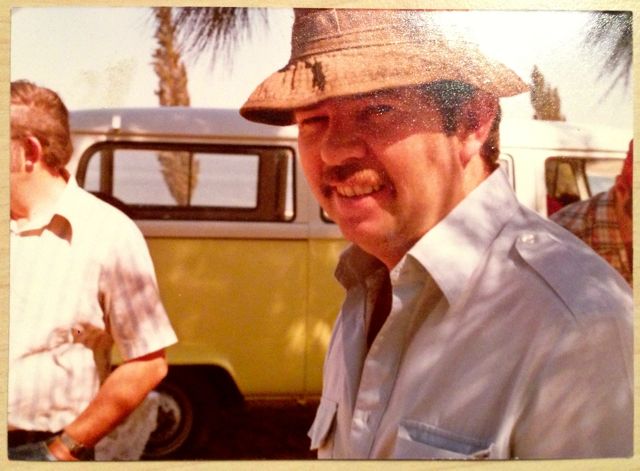

My dad – the biggest heart and warmest hugs hiding behind that brusque exterior – the one that would growl at anything that even thought about threatening a single hair on any of our heads – looked over the candle-lit table at me and said “It was like that up on the Border too – everything was propaganda.”

And I watched my deep-hearted dad drop his head forward ever so slightly, and start talking from a well of darkness in his past:

“The walls of the camps were covered in stuff all telling you that black was bad. And we saw it play out. We saw whole villages gunned down because they were supposedly “die swaart gevaar”. We were trained to kill based on colour. I saw things there that still stay with me. I watched a police colonel drive down a road after I offered to send an anti-mine vehicle ahead of him and he told me to “fok off”. I watched him and the 5 other police-men in that truck get blown up by a landmine not 30 metres down the road because he was an idiot.

“And it was no different when we got home. The propaganda carried on. But here at least we had people like Gavin (Graham – an ex-Methodist minister and Bishop, and a close golfing buddy of my dads). He was a hero in the Free State in my view. I watched him walk into a hostel un-armed where people were killing each other hand-to-hand. People like him were miracles.

“On one hand the army was training us to kill black people, and on the other hand the mines (The Gold mining industry is the biggest employer in the Free State. My dad worked on gold mines for over 40 years) were telling us to nurture and train black people. But it was hard to know what was right in the midst of all the gunfire and flames. I was lucky, I had the church and people like Gavin to bring some sanity.

“I remember going into Thabong (the township outside Welkom) to support the police during one of the riots in the early 80’s and almost ending up in a shoot-out with a Police Captain. He did things I couldn’t condone and eventually after almost getting into a shooting match with him, my guys pulled me out. The army were there to support the police, supposedly, he had the authority, I didn’t.

“I left that day and after that was when I left the army.”

I always wondered what had happened. My dad was a Major in the army – as high as you could get without being Permanent Force – he used to do Cadet training camps, and pretty much run things at the Welkom Commando. My little sister and I sometimes went with when he had to pick up something or lock up and I remember playing on the Casspirs and the other army vehicles standing in the dusty parade ground of the Commando. They were toys to us – funny looking cars and trucks. We knew dad was “in the army” but not what that meant really.

And it took almost 40 years for my dad to tell me just a tiny fraction of what that meant in his life. I’ve known my dad’s huge heart all my life, but I’ve only just begun to understand what it cost him and what living his life has really meant to him. And my mom.

My mom who watched her 28 year old husband of 4 years go to the border and then knew that he was different when he came back. I don’t know how much he ever even told her about what happened, but I know that she spent 3months alone with a baby wondering every second of every day if he was coming back in one piece or at all.

And things were different when he got back. She was committed to being a mom and he had seen things that had changed him. Ten months later my little sister was born. My mom holds back a little but does say “It was a very difficult time for us as a couple and a family.” This from my lovely mother who I have seen almost in tears regretting what she thinks she did wrong as a first-time mother to me. This from a mother who I remember only as the wonderful, loving person who made toast and tea while I did home-work in the sunny patch on my bedroom floor and who can still ease any form of ache with just the warmth of her hand. This from my lovely lovely mother.

And it’s only now with some inkling of what their lives have been shaped by, that I can even start to understand how much more complex it must have been for them to watch and rejoice when the schools were opened in my matric year and I did a ballroom dance with a new, black classmate in our annual school musical. Or to know what to do when the elections changed the country forever a couple of years later and everyone voted and Mandela went from one end of the scale to another. Or to wander what this country would hold for their little boy when he was born years later.

I was always naïve, probably still am in many ways, and partly that was because my parents chose to protect us from the harsh realities of that mid-crisis Free State context we were born into. And even just for that respite, for the grace of having been spared the complexities and horror that they lived through, I am now even more grateful for them than ever before. I am blessed to have these two such special, complex people to guide my way – both then and now.

This week, back in the hurly burly of business busy-ness and life in general, a friend posted this quote on FaceBook:

“Perhaps everyone has a story that could break your heart…” -Nick Flynn

Yes, probably. But the stories of who we are and what we have seen are everything really. They are our immortality. And our contribution.

They remind us.

To listen – listen for the stories of the people we love. Allow them to be told and heard. It doesn’t matter how long it takes, just keep listening and the stories will come eventually. And you will never be sorry – it’ll be worth it, no matter how long you wait.

And to share. They are the tiny nudge that remind us to share our own stories too. Eventually the space will be there for your story to be heard. Don’t be scared to share it – you never know who may be waiting to hear you; to know you better; to love you more. Don’t hold your story in, tell it and you will be surprised by how much you get in return.

Yes, everybody probably has a story that could break your heart. But they will also, almost always, have one to make it whole again.

Who knows, you may even be part of one of those.

April 6th, 2013 at 7:06 pm

Great, Annie. Great story. Thanks for sharing.

April 7th, 2013 at 8:59 am

I find most of you posts move or inspire me Annie. But this one made me cry and also gave me insight that I had not had before. Thank you.

April 7th, 2013 at 10:37 am

oh wow – this is so amazing !!

thanks for sharing …

April 7th, 2013 at 5:45 pm

Wonderful Annie, glad the Kleenex were close by. Thank you, a great Sunday morning story. I am so glad I have met your beautiful warm and loving family.

April 7th, 2013 at 6:06 pm

Thanks for the reminder to ease into a space of listening, my friend.

Makes me want to sit down to a long dinner with my folks again.

April 7th, 2013 at 9:26 pm

Yet another little peak into a moment in time that reveals what makes AJ so special

April 8th, 2013 at 12:10 am

Thanks everyone, this one is close to my heart. Appreciate you all so much.

April 8th, 2013 at 12:14 am

Thanks A. That was wonderful, made me cry.

April 8th, 2013 at 11:24 am

Moms and Dads, such special people to their children and their children’s friends. AJ, you and I had the best Moms on the planet, and quiet Dads with huge hearts! Blessed, both of us!